This past week, I gave a presentation to a group interested in a

particular type of renewable energy–solar energy that is deployed in

space, so it would provide electricity 24 hours per day. Their question

was: how does the production cost of electricity really need to be?

I gave them this two-fold answer:

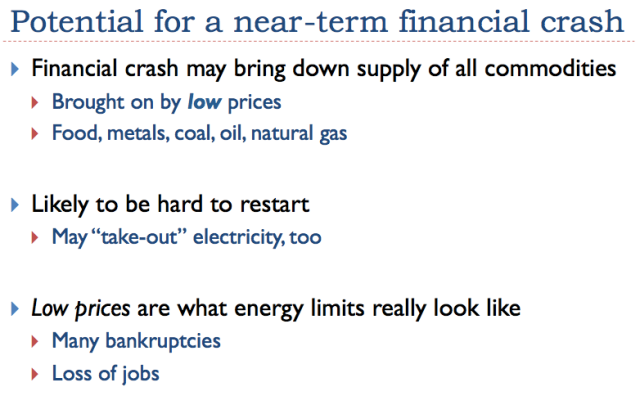

1. We are hitting something similar to “Peak Oil” right now.

The symptoms are the opposite of the ones that most people expected.

There is a glut of supply, and prices are far below the cost of

production. Many commodities besides oil are affected; these include

natural gas, coal, iron ore, many metals, and many types of food. Our

concern should be that low prices will bring down production, quite

possibly for many commodities simultaneously. Perhaps the problem should

be called “Limits to Growth,” rather than “Peak Oil,” because it is a

different type of problem than most people expected.

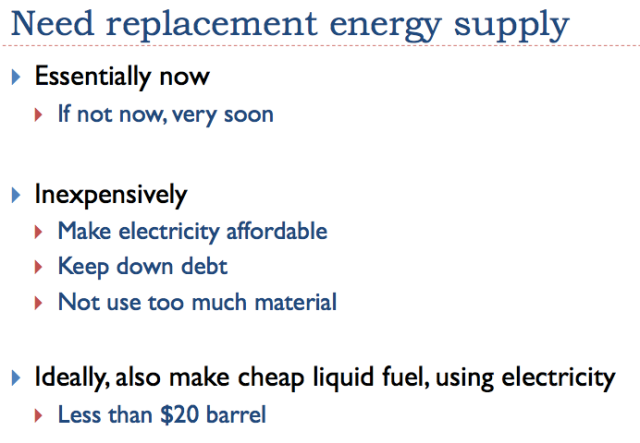

2. The

only theoretical solution would be to create a huge supply of renewable

energy that would work in today’s devices. It would need to be cheap to

produce and be available in the immediate future. Electricity

would need to be produced for no more than four cents per kWh, and

liquid fuels would need to be produced for less than $20 per barrel of

oil equivalent. The low cost would need to be the result of very sparing

use of resources, rather than the result of government subsidies.

Of

course, we have many other problems associated with a finite world,

including rising population, water limits, and climate change. For this

reason, even a huge supply of very cheap renewable energy would not be a

permanent solution.

This is a link to the presentation: Energy Economics Outlook. I will not attempt to explain the slides in detail.

–

Some

people falsely believe that energy supplies are “only needed for

industrial purposes.” Energy supplies are, in fact, needed for many

things: cooking our food, keeping our homes warm, and creating the

clothing we expect to wear. It would be impossible to feed, house, and

clothe 7.3 billion people without supplemental energy of some kind.

–

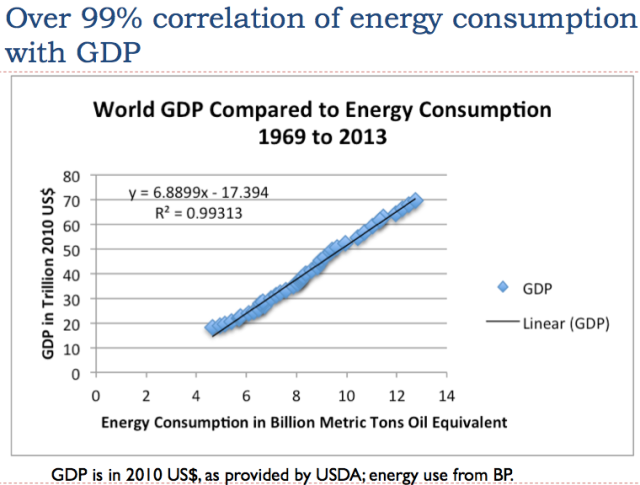

Slide

4 suggests that the world economy is heading into recession, because

recent growth in the use of energy supplies is very low recently.

Another sign that we are headed into recession is that fact that CO2 emissions fell in 2015.

They usually don’t fall unless a global crisis exists. Emissions fell

when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, and they fell during the

economic crisis in 2008. Perhaps the world economy is hitting headwinds

that are not being picked up well in conventional calculations of GDP

growth.

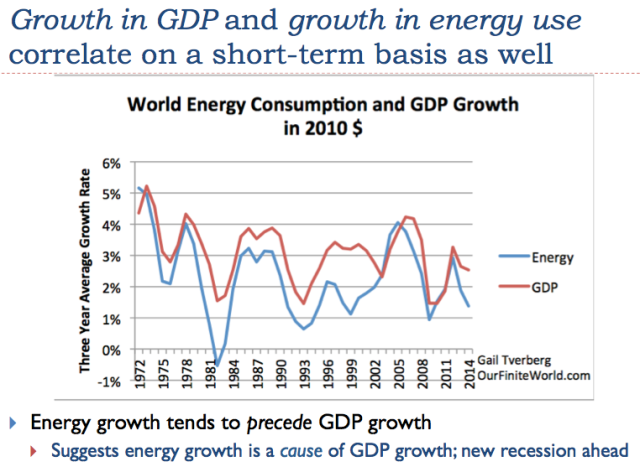

Slide

5 shows a chart I put together, using data from several different

sources, showing how growth in energy consumption has compared with

growth in GDP. Growth in GDP tends to be somewhat higher than growth in

energy consumption.

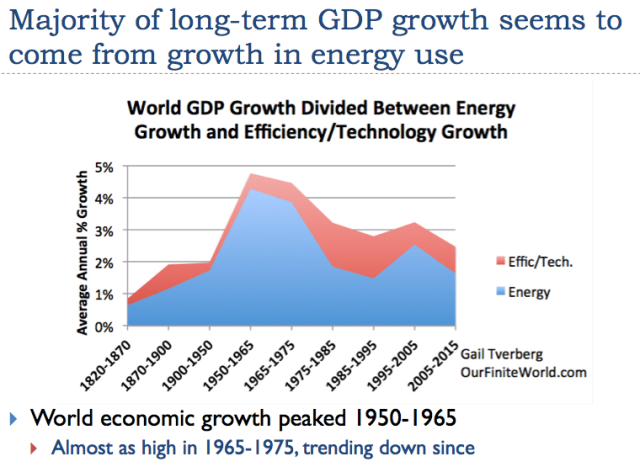

Economic growth (and growth in energy use) was

low prior to 1950. There was a big jump in economic growth immediately

after World War II, in the 1950-65 period. There was almost as much

growth in the 1965- 75 period. Since 1975, economic growth has generally

been slowing.

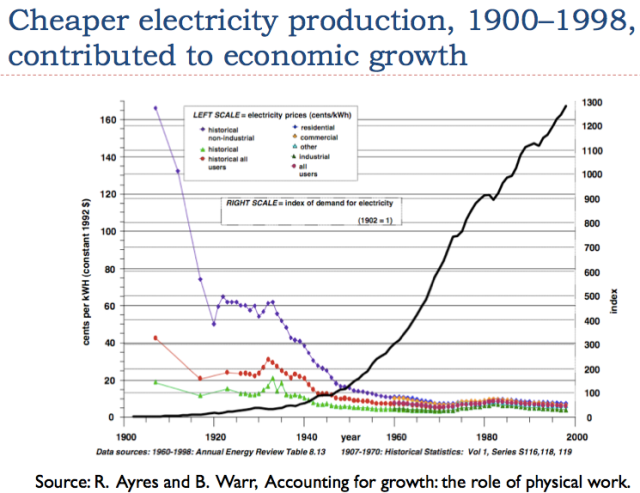

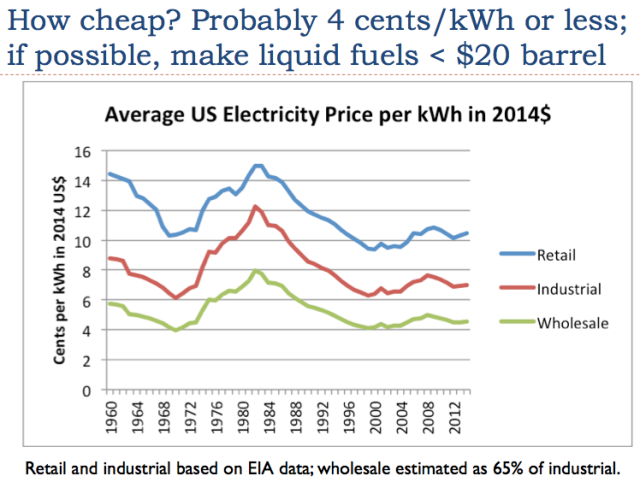

Between

the years 1900 and 1998, the use of electricity rose (black line) as

the cost of electricity fell (purple, red, and green lines). Electricity

consumption could rise because it was becoming more affordable. Rising

electricity consumption allowed the economy to make more goods and

services. Workers (with the use of electricity) were becoming more

efficient, so wages could rise. With higher wages, workers could afford

more products that used electricity, such as electric lights for their

homes and radios.

If electricity prices had risen instead of

fallen, it seems doubtful that this pattern of rising consumption could

have taken place.

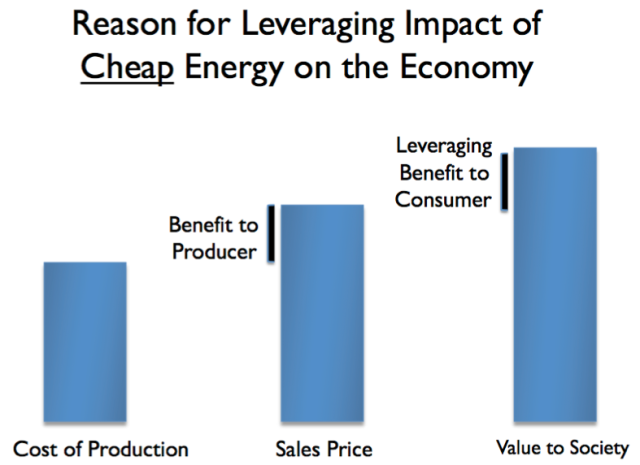

The

comments in Figure 7 represent my own view. It is based on both

theoretical considerations and historical relationships. Many who have

studied the economy believe that energy is important for economic

growth. In my view, the real need is for cheap-to-produce energy, not

just any energy. If cheap energy is not really available, then adding

more debt can somewhat make up for the high cost of energy production.

Debt

is important because it makes goods affordable that would not otherwise

be affordable. For example, having a loan for a house or a car makes a

huge difference regarding whether such an item is affordable. Even

when energy products are cheap, debt seems to be needed to get oil or

coal out of the ground, or to make a new device such as a wind turbine.

Part of the problem is the cost of the capital equipment needed to

extract the oil or coal, or the cost of the wind turbines themselves.

Another part of the problem is paying for factories to make devices that

use the energy product. A third problem is making it possible for users

to afford the end products, such as houses and cars. It is much easier

to borrow the money for a new tractor, and pay the loan off as the

tractor is put to use, than it is to save money in advance, using only

the funds earned when farming with simple hand-held tools.

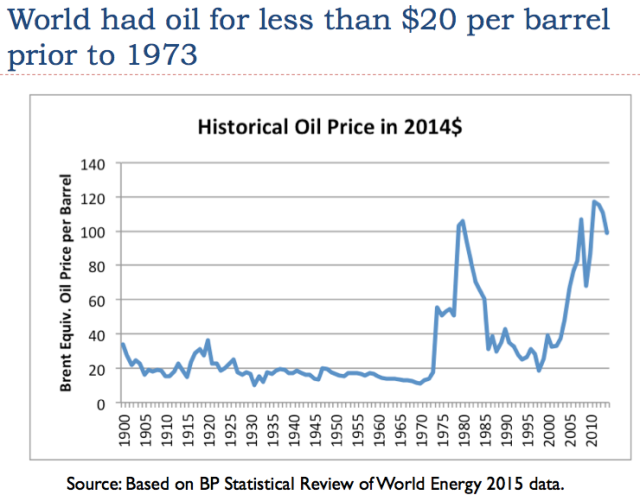

I

mentioned the need for $20 per barrel oil on Slide 7. This is a very

inexpensive price. Slide 8 shows that the only time when oil prices were

that low was prior to the mid-1970s. The cost of oil production is now

far above $20 per barrel. The sales price now is about $37 per barrel.

This is below the price producers need, but still above my target price

level.

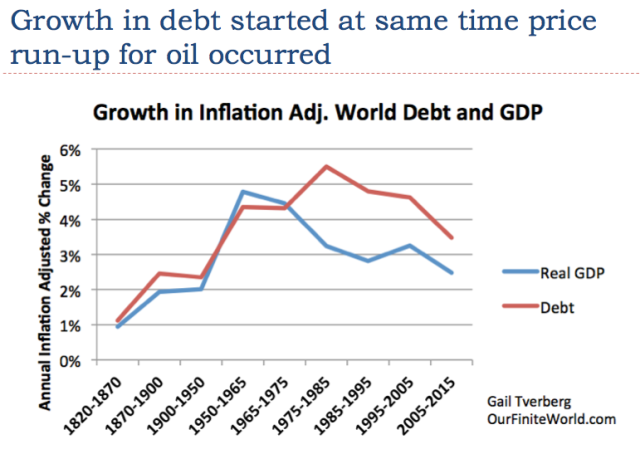

Slide

9 explains where I got my $20 per barrel price target. Back prior to

1975–in other words, back when oil prices were generally low, $20 per

barrel or less–the increase in debt more or less corresponded to the

growth in GDP. Once prices rose above $20 per barrel, the amount of debt

needed to produce a given amount of GDP growth rose dramatically.

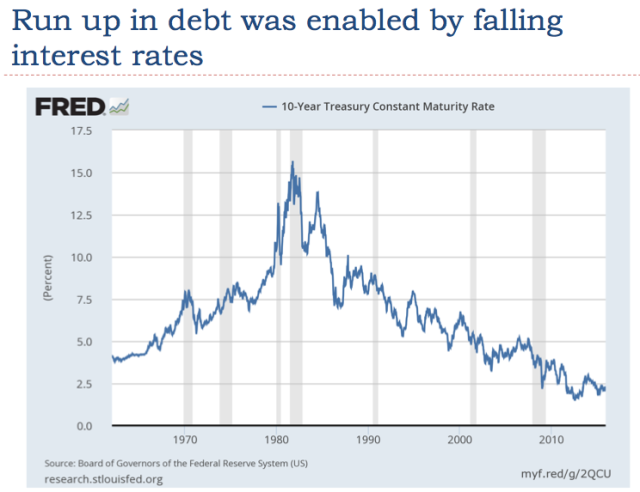

Slide

10 shows interest rates for US debt with 10-year maturity. These

interest rates often underlie mortgage rates. As interest rates fall,

homeowners can afford increasingly expensive homes. If shorter-term

interest rates fall as well, auto loans become cheaper too.

The

value to society of a barrel of oil is determined by how many miles it

can make a diesel truck go, or how far it can make an airplane fly. This

value to society is more or less fixed. The only change is the small

increment each year from efficiency changes, making a barrel of oil “go

farther.”

In the 2000-14 period, the cost of new oil production

was increasing very rapidly–by more than 10% per year, by some

estimates. The rising cost of oil production occurred much more quickly

than efficiency changes. The result was a falling difference between the

value to society and the cost of production. When oil prices are high,

oil-importing nations tend to suffer recession. When oil prices are low,

oil-exporting nations find it hard to collect enough taxes to support

their many programs.

The

fact that we need energy for economic growth means that we somehow must

obtain this energy, even if doing so costs more. The big run-up in oil

prices is a major reason for the historical run-up in debt levels.

China’s big build-out of homes, roads, and factories was also financed

by debt.

The higher cost of oil affects many things that we don’t

think are related, including the cost of building new homes, the cost of

building cars, and the cost of building roads. As consumers are forced

to buy increasingly expensive homes and cars, and as governments find

that the building of roads is increasingly expensive, more debt is used.

The terms of loans are often longer as well, to hold down monthly

costs.

If we still had cheap oil, this oil by itself could provide

a “lift” to the economy. An increasing amount of debt can “sort of”

compensate for the absence of cheap oil.

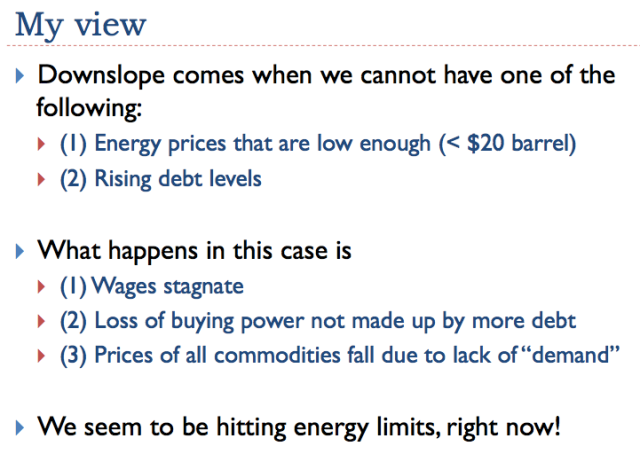

The problem we encounter

is that neither cheap energy nor the continued run-up of debt is

sustainable. Cheap energy tends to change to expensive energy, because

we use the cheapest sources first. The continued debt run-up becomes

more and more difficult to handle, unless interest rates fall lower and

lower. At some point, interest rates can’t fall enough, and the whole

pile of debt tends to collapse, like a Ponzi scheme.

I

gave this talk on December 15; the first increase in interest rates

took place on December 16. With rising interest rates, we suddenly have

“the prop” that was attempting to hold up economic growth taken away.

We

need ever expanding debt–that is, debt rising faster than GDP levels–to

try to keep the world economy growing, so that the whole pile of debt

doesn’t fall over and collapse. If we are to have non-debt growth in the

future (because we are reaching limits on debt), it needs to again come

from cheap energy alone. We need to get back to something similar to

the low-cost energy that fueled the economy before the debt run-up.

Most

of us have heard the Peak Oil story, and assume it represents a

reasonable view of where we are headed. I think it is close to 180

degrees off course.

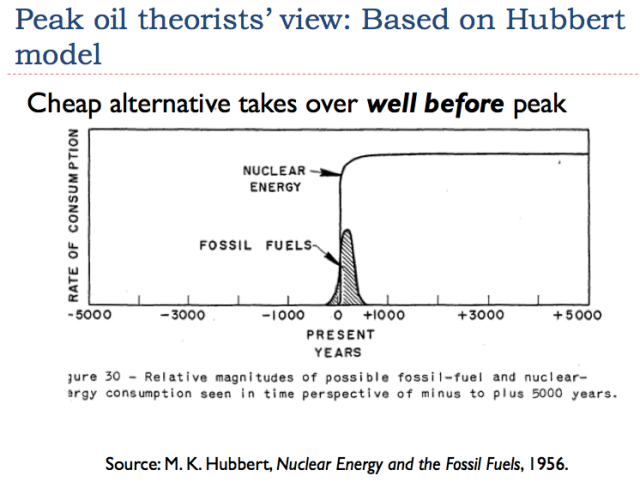

M.

King Hubbert talked about a very special situation–a situation where

another cheap, abundant fuel took over, before fossil fuels began to

decline. In this particular situation (and only

in this particular situation), it is reasonable to assume that

production will follow a symmetric “Hubbert Curve,” with half of the

production coming after the peak, and half beforehand. Otherwise, the

down slope is likely to be much steeper. Many peak oilers missed

this important point. We certainly are not in a situation today where

another very cheap fuel has taken over.

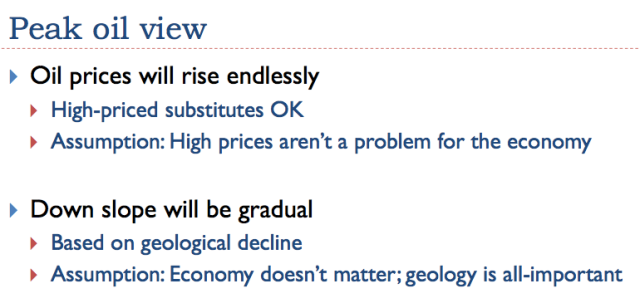

Slide

16 represents what I see as the predominant “Peak Oil” view of the oil

limits situation. Some individuals will of course have different

opinions.

Peak

oilers certainly did get part of the story right–at some point, the

cost of oil extraction would rise. What they got wrong was how the whole

scenario would play out. It turns out, it plays out pretty much the

opposite of what most had supposed–that is, with stagnating wages, loss

of buying power, and prices of all commodities falling because of lack

of “demand.”

We seem to be hitting energy limits, right now. That

is why debt is such a problem, and it is why prices of many commodities,

including oil, are far too low compared to the cost of production.

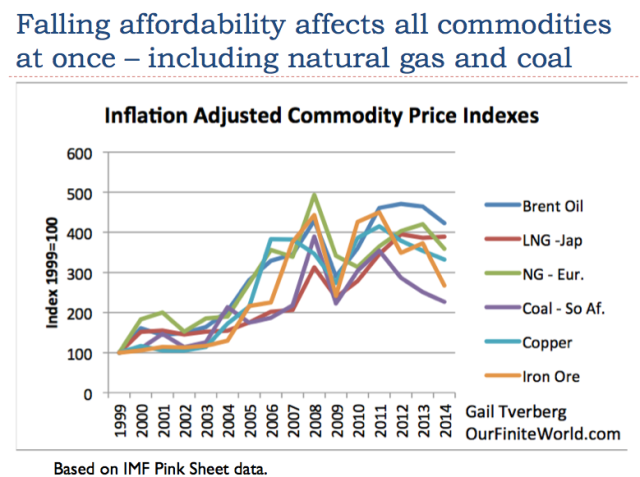

Slide

18 shows the fall of commodity prices up through 2014. The fall in

commodity prices has continued in 2015 as well. The story we frequently

hear is about low oil prices, but there is also a problem with low

natural gas prices. Coal prices are low now too, and, in fact, many coal

producers are near bankruptcy. Prices of iron ore, steel, copper, and

many other metals are very low, as are prices of many kinds of staple

foods traded internationally.

The

problem with low commodity prices is that there are many loans that

have been taken out to support their production. There is a significant

chance of default, if prices remain low. Also, low commodity prices

affect asset prices–for example, prices of coalmines, or prices of

agricultural land. As the prices of commodities fall, the price of the

land used to produce those commodities falls. When this happens, it

becomes difficult to repay the loans on the property.

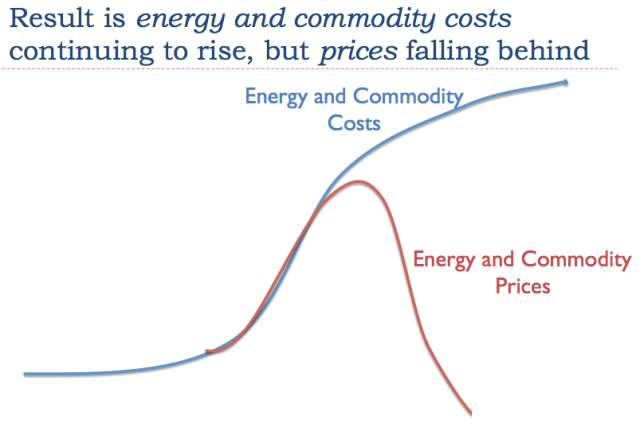

Peak

Oilers were right about the cost of production continuing to rise. What

they missed was the fact that prices would at some point fall behind

the cost of production because of affordability issues. Low prices would

then bring the economy down, as it did in the Depression in the 1930s,

and in quite a few earlier collapses.

I think of increased demand,

provided by debt, as being like a rubber band. Just as a rubber band

can stretch for a while, the price of oil can rise for a while, fueled

by more and more debt. At some point, debt can’t rise any higher–the

rate of return on investments made using debt is too low, and defaults

become too frequent. Instead of continuing to rise, commodity prices

fall back. Market prices of commodities fall to much lower prices than

the costs of production.

In order to get oil prices up higher, the

wages of factory workers, restaurant workers, and other non-elite

workers need to rise, so that they can afford to buy nice cars and nice

homes. Commodities of many types are used both in making homes and cars,

and in operating them.

If

space solar (or for that matter, any renewable energy) is to be

helpful, it needs to be very cheap, so that products made using

renewable energy are affordable.

If the replacement energy source

is cheap enough, perhaps there will not be a huge run-up in debt to GDP

ratios, to finance the new devices used to provide electricity or other

energy.

We are encountering problems now, so we need a replacement now, not 20 or 50 years from now.

We

cannot expect the cost of electricity production to be more than the

current wholesale selling price of electricity. Thus, it needs to be

four cents per kWh or less. Ideally, the price of electricity should be

falling, as in Slide 6.

Another consideration is that we need to

be able to operate our current vehicles using a liquid fuel, made with

electricity, because of the time and materials involved in switching

over to electric vehicles. This requirement likely reduces the maximum

cost of electricity even below four cents per kWh.

It

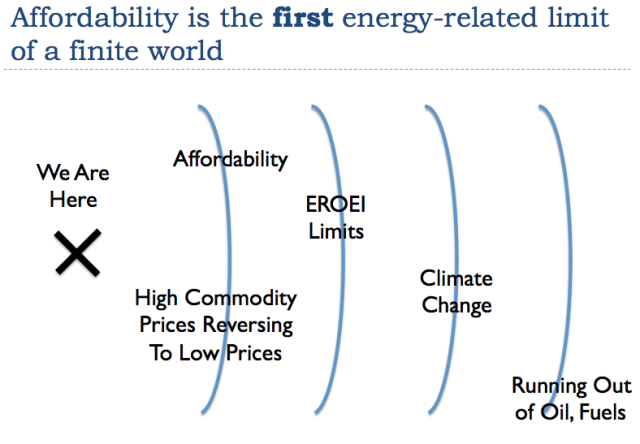

is possible to run into many different kinds of limits, over a period

of time. In my view, the first limit we reach is an affordability limit.

We can tell we are hitting this limit when high prices reverse to low

prices, as they have done since 2011. The fact that prices are

continuing to fall is especially worrisome.

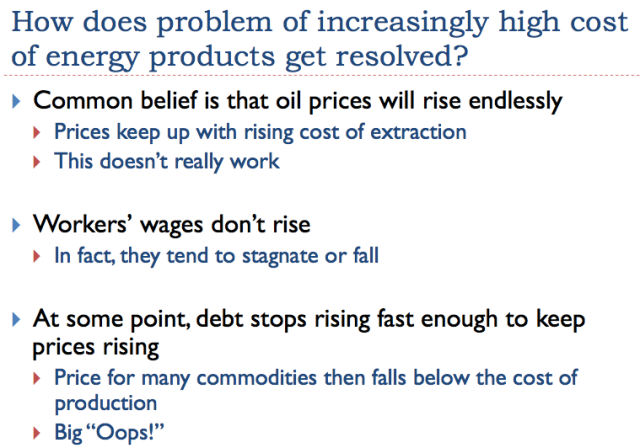

There

has been a popular myth that it is OK for energy costs to rise. We will

just choose the least costly of the high-priced alternatives. This

approach doesn’t really work, because wages do not rise at the same

time.

Also, we have to compete with other countries. If their

energy costs are cheaper, their manufacturing costs are likely to be

lower.

If

conditions existed that allowed oil prices to rise endlessly (in other

words, rising wages of non-elite workers together with debt that could

spiral ever higher, as a percentage of GDP), we wouldn’t really have a

problem–we could afford increasingly expensive substitutes.

Unfortunately, the story of ever-rising oil prices is simply fiction.

It is a pleasant story, but not really true. I explain some of the

issues further in “Why ‘supply and demand’ doesn’t work for oil.”

http://www.theenergycollective.com/gail-tverberg/2304110/we-are-peak-oil-now-we-need-very-low-cost-energy-fix-it

No comments:

Post a Comment