We live in a world with limits, yet our economy needs growth. How

can we expect this scenario to play out? My view is that this problem

will play out as a fairly near-term financial problem, with low oil

prices leading to a fall in oil production. But not everyone comes to

this conclusion. What were the views of early researchers? How do my

views differ?

In my post today, I plan to discuss the first

lecture I gave to a group of college students in Beijing. A PDF of it

can be found here: 1. Overview of Energy Modeling Problem. A MP4 video is available as well on my Presentations/Podcasts Page.

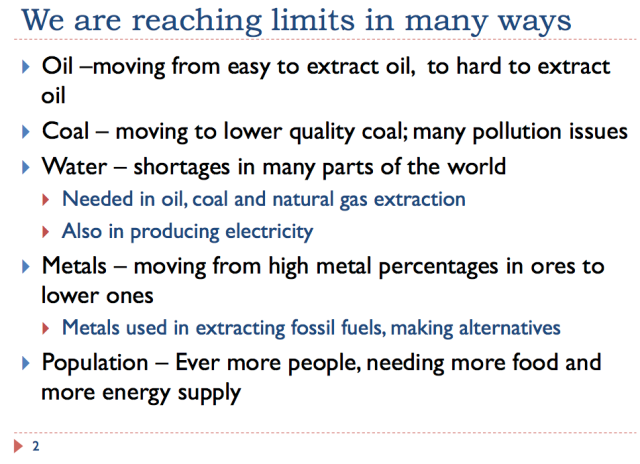

Many Limits in a Finite World

We live in a world with limits. These limits are not just energy limits; they come in many different forms:

All

these limits work together. We can work around these limits, but the

workarounds are higher cost–for example, substituting less polluting

energy resources for more polluting energy resources, or extracting

lower grade ores instead of high-grade ores. When lower grade ores are

used, we need to process more waste material, raising costs because of

greater energy use. When population rises, we must change our

agricultural approaches to increase food production per acre cultivated.

The problem we reach with any of these workarounds is diminishing returns.

We can keep increasing output, but doing so requires disproportionately

more inputs of many kinds (including human labor, mineral resources,

fresh water, and energy products) to produce the same quantity of

output. This creates higher costs, and can lead to financial problems.

This phenomenon is one of the major things that a model of a finite

world should reflect.

Economists Views

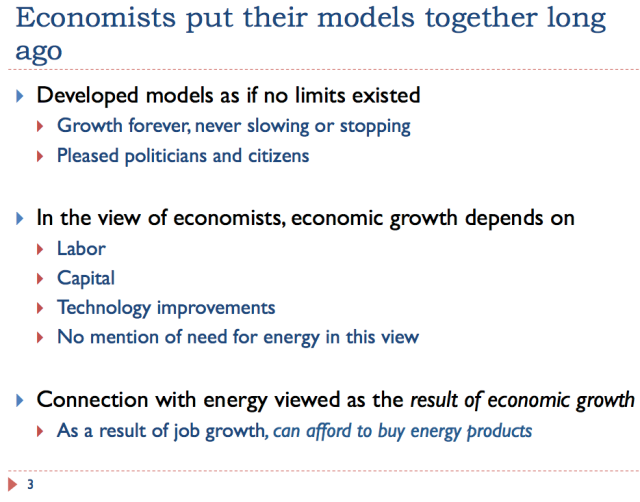

Economists

developed their views of the economy long ago, when limits seemed to be

far in the distance. Thus, the models they built do not reflect the

expected impact of limits. They are missing variables that would be

needed to adjust for changes in the economy’s behavior as limits are

reached.

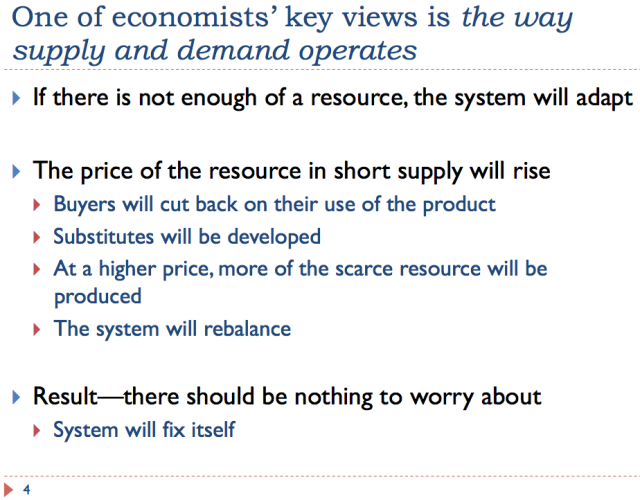

The

story in Slides 3 and 4 tends to be true if we are far from limits, but

is it really true when we are close to limits? Perhaps diminishing

returns as we approach limits changes the results.

World Oil Situation as We Approach Limits

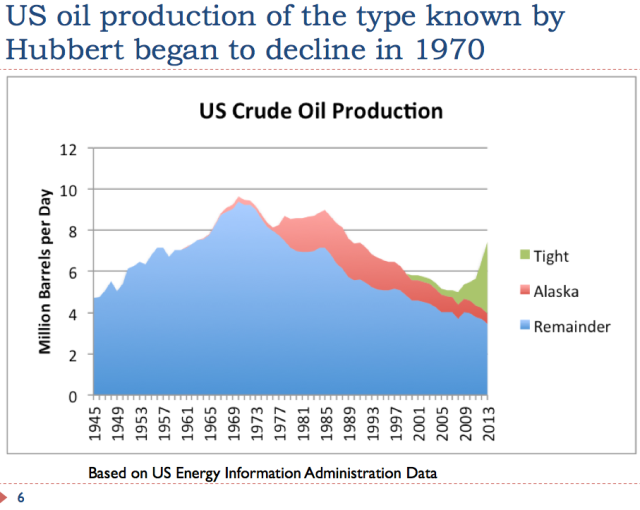

Perhaps

we can get some indication of how diminishing returns are affecting the

economy by looking at historical oil supply and prices. Up until 1970,

US oil production grew quite steadily.

After

1970, oil production suddenly began to decline. Oil companies did not

expect such a decline; they assumed that oil production would rise

endlessly. Once oil production began to decline, oil companies quickly

began trying to find ways to fix their problems. One of these approaches

was quickly to ramp up production in areas that they knew contained

oil, but hadn’t previously been drilled. These included Alaska (northern

United States), Mexico, and the North Sea. Oil production in these

areas is now in decline.

Several ways were also found to reduce

oil usage. These included change from oil to alternate fuels for

electricity generation and home heating, and offering smaller, more

fuel-efficient cars. With this combination of approaches, oil prices

were brought down, most of the way to the $20 level (Slide 7).

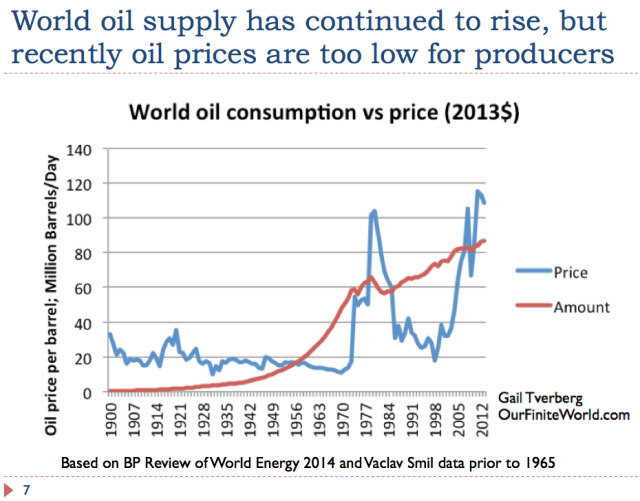

The

inflation adjusted level of oil prices is important because oil is the

single largest source of energy use in both the US and world economy. If

oil prices are cheap, it easy to grow food cheaply, and manufacturing

and transport can be done cheaply. Because of this, the economy tends to

grow. If oil prices rise, economic growth tends to slow, because the

cost of many types of goods (including oil products, food, and building

new homes) tends to rise faster than wages. It becomes more expensive to

replace infrastructure such as roads and pipelines as well. The higher

cost of oil effectively acts as a “tax” inhibiting economic growth.

Oil

prices again reached a high level in the early 200os as we again began

to reach limits of the amount of oil that could be extracted at the

then-available price. This time we weren’t able to cut back on world

demand, so prices tended to stay high. Instead, the big change made was

in oil supply, with higher oil prices enabling (after a several years

time-lag) greater production both from US oil from shale formations

(called “tight oil” in Slide 6 above) and from the oil sands in Canada.

The

question becomes: can the economy really function adequately on $100+

barrel oil? Or do the negative feedbacks from these high oil prices have

too adverse an impact on economic growth?

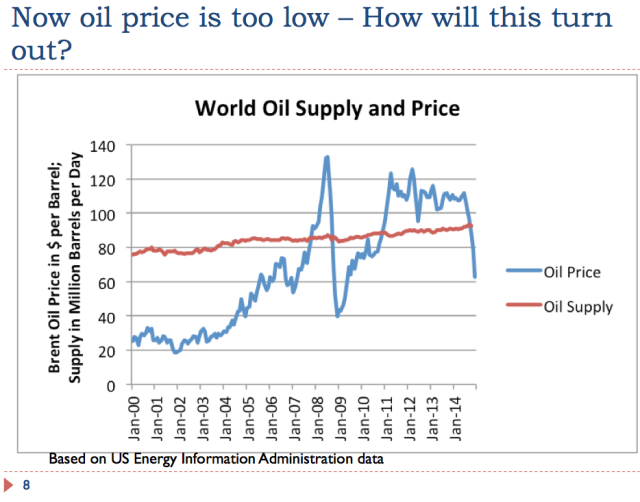

Slide

8 shows more detail regarding production and prices for recent years.

We see that oil prices were generally rising up until mid 2008, and then

dropped steeply. Prices rose again after several types of economic

stimulus were added. More government spending was added, interest rates

were dropped to very low levels and a program called quantitative easing

(QE) began.

Prices stayed at a level a little over $100 barrel

from January 2011 though mid-2014. More recently, oil prices have

dropped to a little more than half of their previous level. This decline

in oil prices appears to correspond to a time when world debt is not

rising as rapidly: the US stopped its QE program, and China’s debt no

longer rising as rapidly. Thus, some of the economic stimulus that

helped hold oil prices up is disappearing.

The problem we are now

encountering is not the high price problem that economists thought would

bring on more supply. Instead, we are encountering a problem with oil

prices that are too low for oil producers to make a profit. Such low oil

prices can quite possibly bring down world oil production, because

investment in oil production is no longer profitable. A person might

ask: Is the low price situation we saw in 2008 and are encountering

again in 2014-2015 what diminishing returns really looks like? Is the problem we encounter as we reach limits one in which oil prices drop too low, rather than rise too high?

In

2008, huge stimulus efforts were required to bring oil prices were

brought back up to the $100+ level. Perhaps one point raised by

economists (Slide 3) was correct: Maybe there is a connection between

economic growth and oil demand. Perhaps the issue as we reach limits is that world economic growth sinks too low,

and it is because of this slow growth that wages stagnate, debt stops

rising quickly, and oil (and other commodity) prices drop too low.

Now let’s look at what some early energy researchers have said.

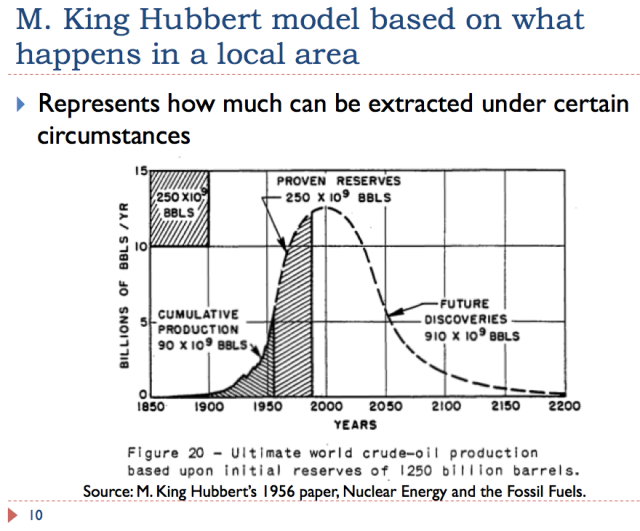

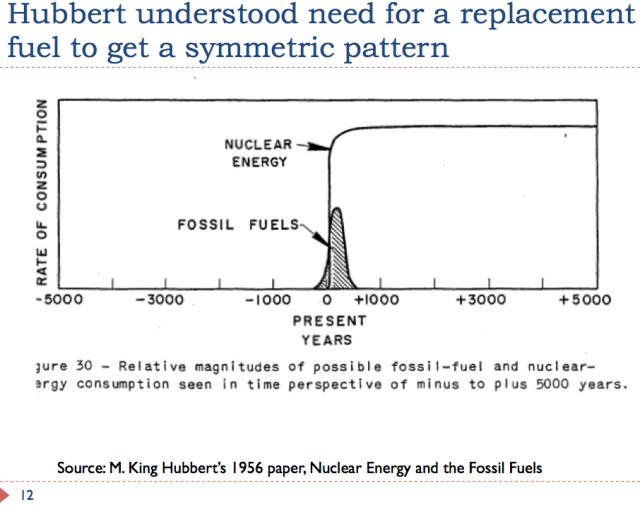

M. King Hubbert

Many

believers in Peak Oil theory consider M. King Hubbert to be the

originator of their theory. It seems to me, though, that Peak Oilers

have inadvertently picked up some of the economists’ theories, and mixed

them with Hubbert’s theories.

It

seems to me that the only way a Hubbert Curve might happen is if oil

prices stay high, as we approach limits. That way, as much oil as

possible can be extracted. If oil prices fall too low, then the decline

may be much quicker. If low oil prices are a problem, above ground

problems such as governments of oil exporting nations collapsing, or

rising debt defaults leading to bank failures, may be a problem.

Dennis Meadows and Donella Meadows

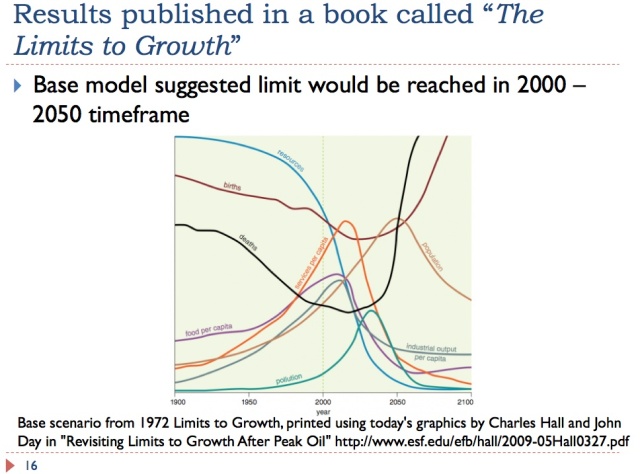

Dennis

Meadows led early computer modeling efforts at MIT regarding limits of a

finite world. His wife, Donella Meadows, led the write-up effort

regarding this model in a 1972 book called “Limits to Growth”. The model

looked at physical quantities of resources, expected amounts of

pollution, and expected population trends. The base model suggested that

the world would start reaching limits in roughly the current timeframe.

In fact, more recent analyses suggest that the base model is more or less on track.

I don’t think that we can count directly on this analysis, however.

Charles Hall

Prof.

Charles Hall has been one of the recent thought-leaders with respect to

oil limits and how they might play out. He started work in the early

1970s as an ecologist, studying the energy patterns of fish. When he

read about the possibility of energy shortages that might occur in the

1972 book Limits to Growth, he tried to adapt an approach used

for studying energy patterns of fish to the world of energy production.

The result was new way of measuring the efficiency of a particular

energy product, called Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI).

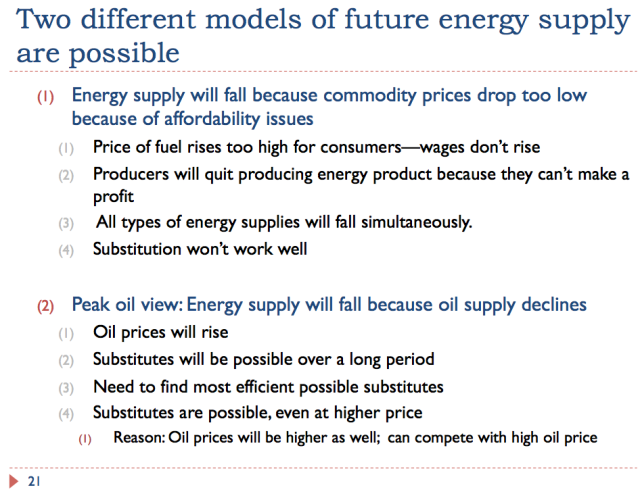

This

idea was an advance when it was first developed, but it has a number of

practical difficulties. One of these difficulties is that its

usefulness is tied to a particular view of how oil limits will affect

us, namely that prices will rise, and this will allow a slow transition

to alternative fuels that are less favorable in terms of EROEI. On Slide

21, this is Item (2).

At

this point, it is my view that the EROEI approach to analyzing energy

products can be misleading and needs updating. Energy extraction is much

more complicated than the energy use of fish swimming upstream. The

EROEI approach, besides being tied to the Peak Oil view of how limits

will occur, is difficult to calculate. Different researchers get quite

different answers, when analyzing the same energy product.

At

this point, it is my view that the EROEI approach to analyzing energy

products can be misleading and needs updating. Energy extraction is much

more complicated than the energy use of fish swimming upstream. The

EROEI approach, besides being tied to the Peak Oil view of how limits

will occur, is difficult to calculate. Different researchers get quite

different answers, when analyzing the same energy product.

Furthermore,

EROEI looks at a piece of energy costs (those involved with production

at the well head), but how this piece relates to the total varies from

one type of energy to another. It lumps together cheap energy and

expensive energy. There are several other issues as well, with the

result being that in practice, low EROEI doesn’t necessarily correspond

to expensive to produce, and high EROEI doesn’t necessarily correspond to low cost to produce.

I

should point out that the same problem exists with a wide range of

similar metrics including Life Cycle Analysis, Energy Payback Period,

and Net Energy. In practice, what seems to happen is that if an energy

type is high-priced, the use of one of these metrics is used to justify

its production, anyhow. Low EROEI (for example, of biofuels) does not

seem to be a barrier to production, even though it was the hope of Prof.

Hall and other EROEI researchers that this would be the case.

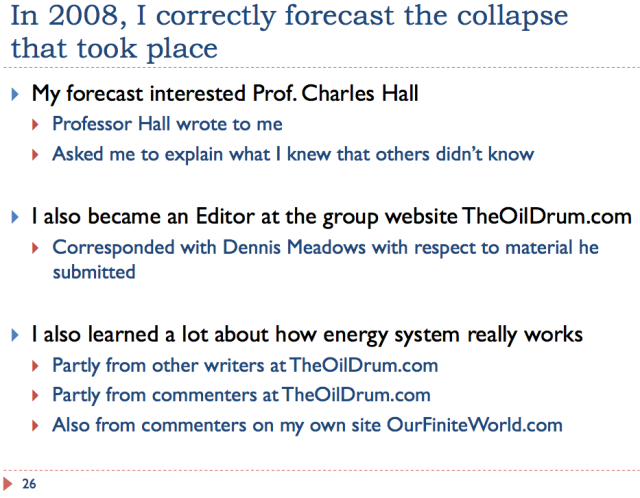

My Involvement in Energy Analysis

I

became acquainted with Prof. Lianyong Feng in 2009, when he attended

the Biophysical Economics Conference in Syracuse, New York, held by

Prof. Charles Hall, and heard me speak.

How Do Oil Limits Really Affect the Economy?

This is the question I have been working on. I will try to explain some of my findings in the next several sessions.

Early

researchers were handicapped because the issue of oil limits crosses

many different fields of research. They took approaches from their own

areas of study, and worked with them. These approaches offered partial

insight into the problem, but didn’t completely answer what might happen

in the future.

It was not obvious to early researchers which

parts of economists’ theories were wrong. I have had the benefit of

seeing how the system works in practice in several periods: in

1973-1974, in 2008-2009, and now in 2014-2015. I have also been

fortunate enough to find a number of recent studies that add new

insights as to how the system really works. So I have taken a step back

and developed at the least the start of a new theory, which is different

from EROEI theory. This is what I will discuss in the next few

sessions.

A little explanation behind this series of lectures and

my four week stay in China is perhaps in order. When I was in China,

Prof. Feng discussed with me some of his intent behind asking me to give

this series of lectures. Prof. Hall is now retired, and there is no

obvious replacement for him. Prof. Feng would like me to take a more

active role is figuring out in which direction energy research should

now be headed, both for his own staff, and for others around the world. A

better understanding of how the system works could theoretically help

researchers everywhere.

http://theenergycollective.com/gail-tverberg/2220661/overview-our-energy-modeling-problem

No comments:

Post a Comment