Most people believe that low oil prices are good for the United

States, since the discretionary income of consumers will rise. There is

the added benefit that Peak Oil must be far off in the distance, since

“Peak Oilers” talked about high oil prices. Thus, low oil prices are

viewed as an all around benefit.

In fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Peak Oil story we have been told is wrong. The collapse in oil production comes from oil prices that are too low, not too high. If

oil prices or prices of other commodities are too low, production will

slow and eventually stop. Growth in the world economy will slow,

lowering inflation rates as well as economic growth rates. We

encountered this kind of the problem in the 1930s. We seem to be headed

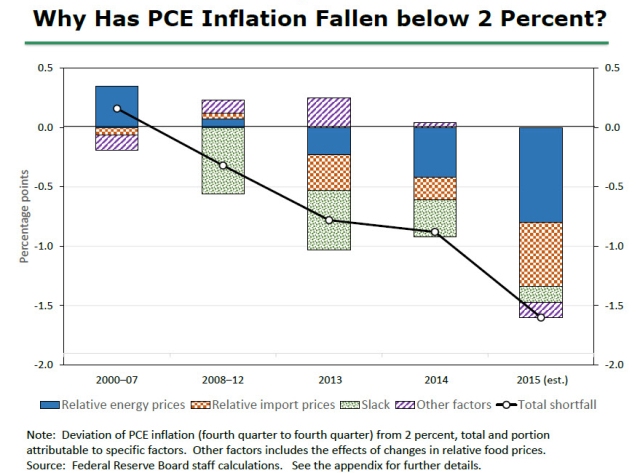

in the same direction today. Figure 1, used by Janet Yellen in her September 24 speech,

shows a slowing inflation rate for Personal Consumption Expenditures

(PCE), thanks to lower energy prices, lower relative import prices, and

general “slack” in the economy.

Figure 1. “Why has PCE Inflation fallen below 2%?” from Janet Yellen speech, September 24, 2015.

What

Janet Yellen is seeing in Figure 1, even though she does not recognize

it, is evidence of a slowing world economy. The economy can no longer

support energy prices as high as they have been, and they have gradually

retreated. Currency relativities have also readjusted, leading to lower

prices of imported goods for the United States. Both lower energy

prices and lower prices of imported goods contribute to lower inflation

rates.

Instead of reaching “Peak Oil” through the limit of high

oil prices, we are reaching the opposite limit, sometimes called “Limits

to Growth.” Limits to Growth describes the situation when an economy

stops growing because the economy cannot handle high energy prices. In

many ways, Limits to Growth with low oil prices is worse than Peak Oil

with high oil prices. Slowing economic growth leads to commodity prices

that can never rebound by very much, or for very long. Thus, this

economic malaise leads to a fairly fast cutback in commodity production.

It can also lead to massive debt defaults.

Let’s look at some of the pieces of our current predicament.

Part

1. Getting oil prices to rise again to a high level, and stay there, is

likely to be difficult. High oil prices tend to lead to economic

contraction.

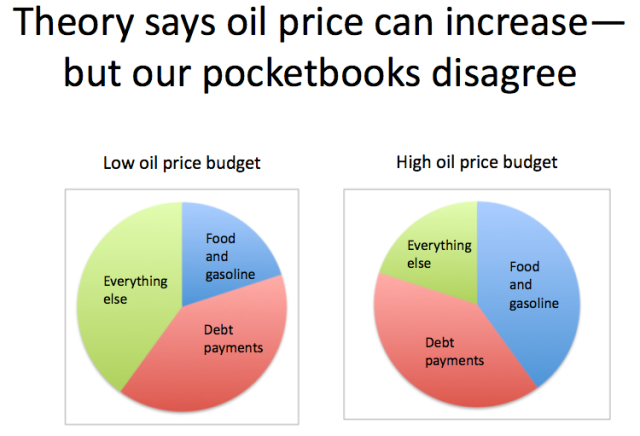

Figure 2 shows an illustration I made over five years ago:

Figure 2. Chart made by author in Feb. 2010, for an article called Peak Oil: Looking for the Wrong Symptoms.

Clearly

Figure 2 exaggerates some aspects of an oil price change, but it makes

an important point. If oil prices rise–even if it is after prices have

fallen from a higher level–there is likely to be an adverse impact on

our pocketbooks. Our wages (represented by the size of the circles)

don’t increase. Fixed expenses, including mortgages and other debt

payments, don’t change either. The expenses that do increase in price

are oil products, such as gasoline and diesel, and food, since oil is

used to create and transport food. When the cost of food and gasoline

rises, discretionary spending (in other words, “everything else”)

shrinks.

When discretionary spending gets squeezed, layoffs are

likely. Waitresses at restaurants may get laid off; workers in the home

building and auto manufacturing industries may find their jobs

eliminated. Some workers who get laid off from their jobs may default on

their loans causing problems for banks as well. We start the cycle of

recession and falling oil prices that we should be familiar with, after

the crash in oil prices in 2008.

So instead of getting oil prices

to rise permanently, at most we get a zigzag effect. Oil prices rise for

a while, become hard to maintain, and then fall back again, as

recessionary influences tend to reduce the demand for oil and bring the

price of oil back down again.

Part 2. The world economy

has been held together by increasing debt at ever-lower interest rates

for many years. We are reaching limits on this process.

Back

in the second half of 2008, oil prices dropped sharply. A number of

steps were taken to get the world economy working better again. The US

began Quantitative Easing (QE) in late 2008. This helped reduce

longer-term interest rates, allowing consumers to better afford homes

and cars. Since building cars and homes requires oil (and cars require

oil to operate as well), their greater sales could stimulate the

economy, and thus help raise demand for oil and other commodities.

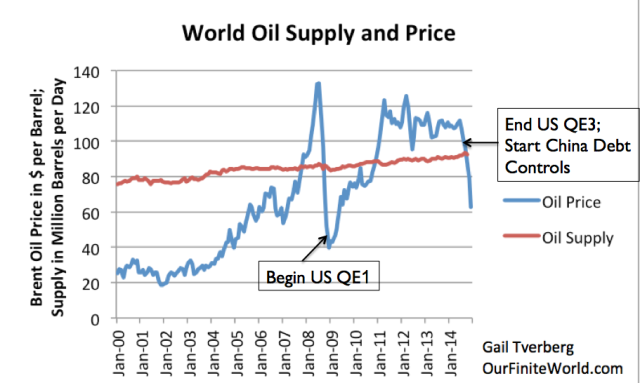

Figure

3. World Oil Supply (production including biofuels, natural gas

liquids) and Brent monthly average spot prices, based on EIA data.

Figure

3. World Oil Supply (production including biofuels, natural gas

liquids) and Brent monthly average spot prices, based on EIA data.

Following the 2008 crash, there were other stimulus efforts as well. China, in particular, ramped up its debt after 2008, as did many governments around the world.

This additional governmental debt led to increased spending on roads

and homes. This spending thus added to the demand for oil and helped

bring the price of oil back up.

These stimulus effects gradually

brought prices up to the $120 per barrel level in 2011. After this,

stimulus efforts gradually tapered. Oil prices gradually slid down

between 2011 and 2014, as the push for ever-higher debt levels faded.

When the US discontinued its QE and China started scaling back on the

amount of debt it added in 2014, oil prices began a severe drop, not too

different from the way they dropped in 2008.

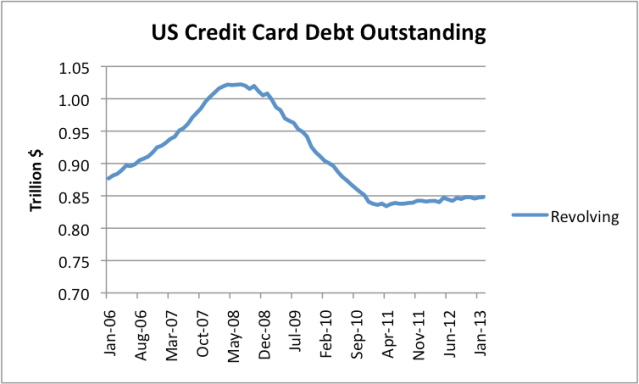

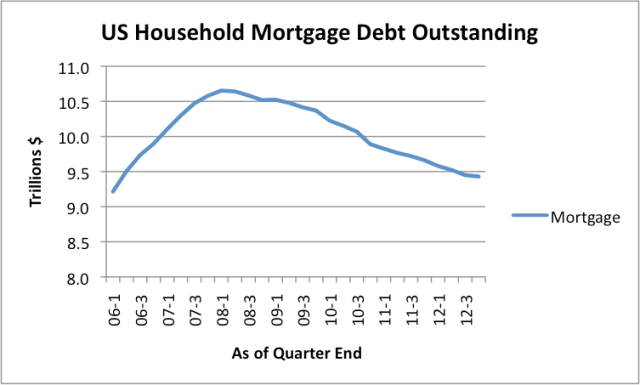

I reported earlier

that the July 2008 crash corresponded with a reduction in debt levels.

Both US credit card debt (Fig. 4) and mortgage debt (Fig. 5) decreased

at precisely the time of the 2008 price crash.

Figure 4. US Revolving Debt Outstanding (mostly credit card debt) based on monthly data from the Federal Reserve.

Figure 4. US Revolving Debt Outstanding (mostly credit card debt) based on monthly data from the Federal Reserve.

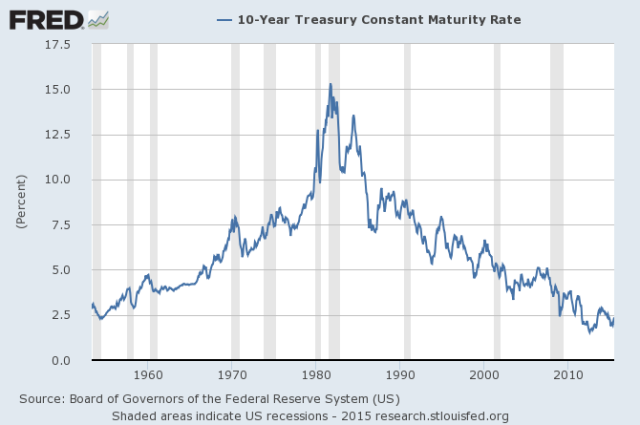

At

this point, interest rates are at record low levels; they are even

negative in some parts of Europe. Interest rates have been falling since

1981.

I showed in a recent post (How our energy problem leads to a debt collapse problem)

that when the cost of oil production is over $20 per barrel, we need

ever-higher debt ratios to GDP to produce economic growth. This need for

ever-rising debt contributes to our inability to keep commodity prices

high enough to satisfy the needs of commodity producers.

Part

3. We are reaching a demographic bottleneck with the “baby boomers”

retiring. This demographic bottleneck causes an adverse impact on the demand for commodities.

Demand represents the amount of goods customers can afford.

The amount consumers can afford doesn’t necessarily rise endlessly. One

of the problems leading to falling demand is falling inflation-adjusted

median wages. I have written about this issue previously in How Economic Growth Fails.

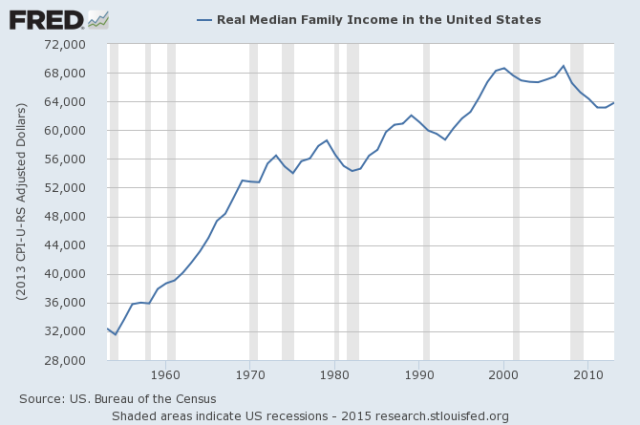

Figure 7. Median Inflation-Adjusted Family Income, in chart prepared by the Federal Reserve of St. Louis.

Figure 7. Median Inflation-Adjusted Family Income, in chart prepared by the Federal Reserve of St. Louis.

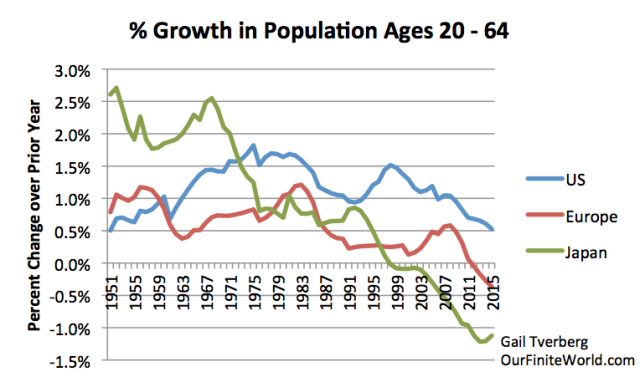

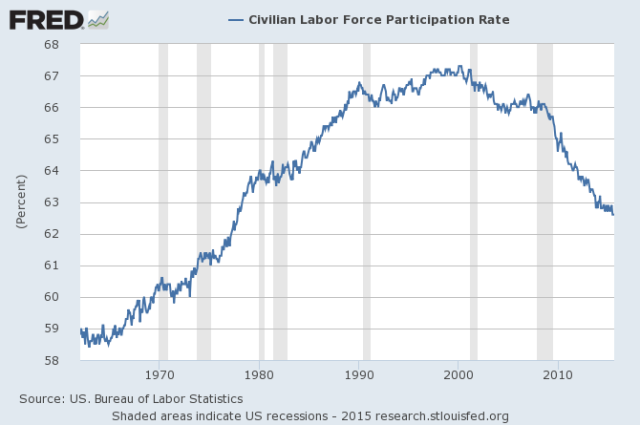

Another

part of the problem of falling demand is a falling number of

working-age individuals–something I approximate by using estimates of

the population aged 20 to 64. Figure 8 shows how the population of these

working-age individuals has been changing for the United States,

Europe, and Japan.

Figure 8. Annual percentage growth in population aged 20 – 64, based on UN 2015 population estimates.

Figure 8. Annual percentage growth in population aged 20 – 64, based on UN 2015 population estimates.

Figure

8 indicates that Japan’s working age population started shrinking in

1998 and now is shrinking by more than 1.0% per year. Europe’s working

age population started shrinking in 2012. The United States’ working age

population hasn’t started shrinking, but its rate of growth started

slowing in 1999. This slowdown in growth rate is likely part of the

reason that labor force participation rates have been falling in the

United States since about 1999.

When

there are fewer workers, the economy has a tendency to shrink. Tax

levels to pay for retirees are likely to start increasing. As the ratio

of retirees rises, those still working find it increasingly difficult to

afford new homes and cars. In fact, if the population of workers aged

20 to 64 is shrinking, there is little need to add new homes for this

group; all that is needed is repairs for existing homes. Many retirees

aged 65 and over would like their own homes, but providing separate

living quarters for this population becomes increasingly unaffordable,

as the elderly population becomes greater and greater, relative to the

working age population.

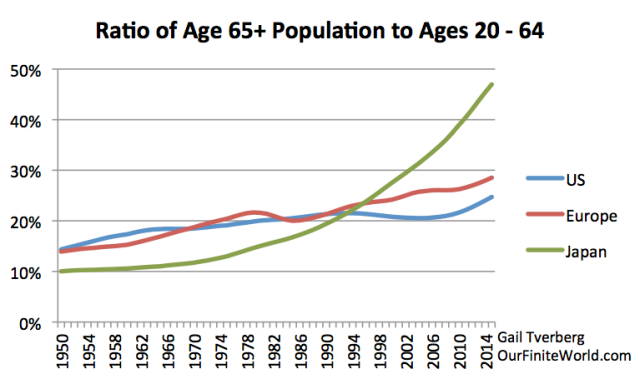

Figure 10 shows that the population aged

65 and over already equals 47% of Japan’s working age population. (This

fact no doubt explains some of Japan’s recent financial difficulties.)

The ratios of the elderly to the working age population are lower for

Europe and the United States, but are trending higher. This may be a

reason why Germany has been open to adding new immigrants to its

population.

Figure 10. Ratio of elderly (age 65+) to working age population (aged 20 to 64) based on UN 2015 population estimates.

Figure 10. Ratio of elderly (age 65+) to working age population (aged 20 to 64) based on UN 2015 population estimates.

For

the Most Developed Regions in total (which includes US, Europe, and

Japan), the UN projects that those aged 65 and over will equal 50% of

those aged 20 to 64 by 2050. China is expected to have a similar

percentage of elderly, relative to working age (51%), by 2050. With such

a large elderly population, every two people aged 20 to 64 (not all of

whom may be working) need to be supporting one person over 65, in

addition to the children whom they are supporting.

Demand for

commodities comes from workers having income to purchase goods that are

made using commodities–things like roads, new houses, new schools, and

new factories. Economies that are trying to care for an increasingly

large percentage of elderly citizens don’t need a lot of new houses,

roads and factories. This lower demand is part of what tends to hold

commodity prices down, including oil prices.

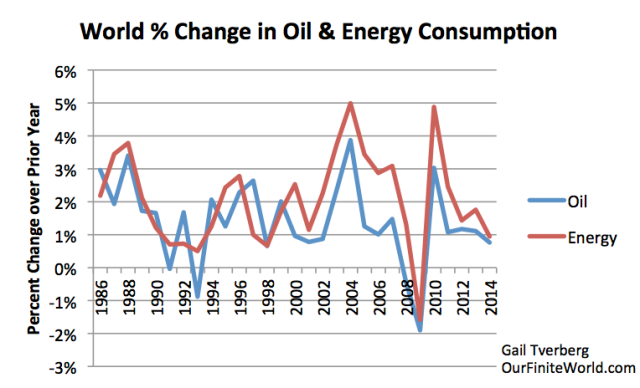

Part 4. World oil demand, and in fact, energy demand in general, is now slowing.

If

we calculate energy demand based on changes in world consumption, we

see a definite pattern of slowing growth (Fig.11). I commented on this

slowing growth in my recent post, BP Data Suggests We Are Reaching Peak Energy Demand.

Figure 11. Annual percent change in world oil and energy consumption, based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 data.

Figure 11. Annual percent change in world oil and energy consumption, based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 data.

The

pattern we are seeing is the one to be expected if the world is

entering another recession. Economists may miss this point if they are

focused primarily on the GDP indications of the United States.

World

economic growth rates are not easily measured. China’s economic growth

seems to be slowing now, but this change does not seem to be fully

reflected in its recently reported GDP. Rapidly changing financial

exchange rates also make the true world economic growth rate harder to

discern. Countries whose currencies have dropped relative to the dollar

are now less able to buy our goods and services, and are less able to

repay dollar denominated debts.

Part 5. The low price

problem is now affecting many commodities besides oil. The widespread

nature of the problem suggests that the issue is a demand

(affordability) problem–something that is hard to fix.

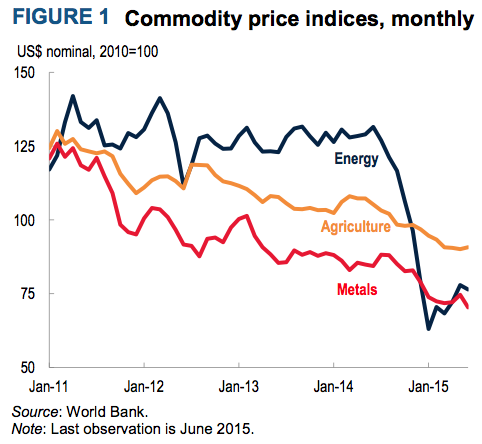

Many

people focus only on oil, believing that it is in some way different

from other commodities. Unfortunately, nearly all commodities are

showing falling prices:

Figure 12. Monthly commodity price index from Commodity Markets Outlook, July 2015. Used under Creative Commons license.

Figure 12. Monthly commodity price index from Commodity Markets Outlook, July 2015. Used under Creative Commons license.

Energy

prices stayed high longer than other prices, perhaps because they were

in some sense more essential. But now, they have fallen as much as other

prices. The fact that commodities tend to move together tends to hold

over the longer term, suggesting that demand (driven by growth in debt, working age population, and other factors) underlies many commodity price trends simultaneously.

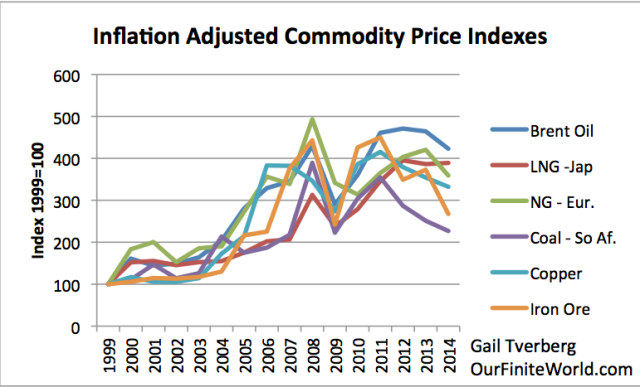

Figure 13. Inflation adjusted prices adjusted to 1999 price = 100, based on World Bank “Pink Sheet” data.

Figure 13. Inflation adjusted prices adjusted to 1999 price = 100, based on World Bank “Pink Sheet” data.

The pattern of many commodities moving together is what we would expect if there were a demand problem leading to low prices. This demand problem would likely reflect several issues:

- The world economy cannot tolerate high priced energy because of the problem shown in Figure 2. We have increasingly used cheaper debt and larger quantities of debt to cover this basic problem, but are running out of fixes.

- The cost of producing energy products keeps trending upward, because we extracted the cheap-to-produce oil (and coal and natural gas) first. We have no alternative but to use more expensive-to-produce energy products.

- Many costs other than energy costs have been trending upward in inflation-adjusted terms, as well. These include fresh water costs, the cost of metal extraction, the cost of mitigating pollution, and the cost of advanced education. All of these tend to squeeze discretionary income in a pattern similar to the problem indicated in Figure 2. Thus, they tend to add to recessionary influences.

- We are now reaching a working population bottleneck as well, as described in Part 4.

Part

6. Oil prices seem to need to be under $60 barrel, and perhaps under

$40 barrel, to encourage demand growth in US, Europe, and Japan.

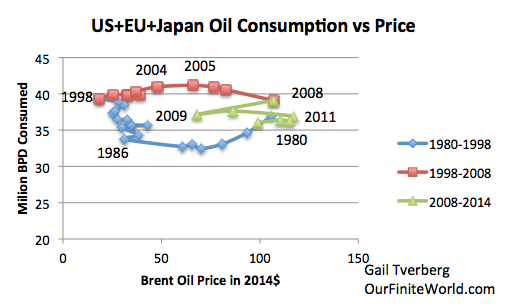

If

we look at the historical impact of oil prices on consumption for the

US, Europe, and Japan combined, we find that whenever oil prices are

above $60 per barrel in inflation-adjusted prices, consumption tends to

fall. Consumption tends to be flat in the $40 to $60 per barrel range.

It is only when prices are in the under $40 per barrel range that

consumption has generally risen.

Figure 14. Historical consumption vs. price for the United States, Japan, and Europe. Based on a combination of EIA and BP data.

Figure 14. Historical consumption vs. price for the United States, Japan, and Europe. Based on a combination of EIA and BP data.

There

is virtually no oil that can be produced in the under $40 barrel

range–or even in the under $60 barrel a range, if tax needs of

governments are included. Thus, we end up with non-overlapping ranges:

- The amount that consumers in advanced economies can afford.

- The amount the producers, with their current high-cost structure, actually need.

One

issue, with lower oil prices, is, “What kinds of uses do the lower oil

prices encourage?” Clearly, no one will build a new factory using oil,

unless the price of oil is expected to be sufficiently low over the

long-term for this use. Thus, adding industry will likely be difficult,

even if the price of oil drops for a few years. We also note that the

United States seems to have started losing its industrial production in

the 1970s (Fig. 15), as its own oil production fell. Apart from the

temporarily greater use of oil in shale drilling, the trend toward

off-shoring industrial production will likely continue, regardless of

the price of oil.

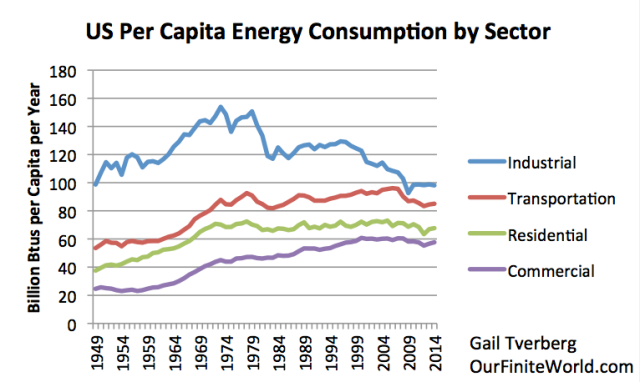

Figure

15. US per capita energy consumption by sector, based on EIA data.

Includes all types of energy, including the amount of fossil fuels that

would need to be burned to produce electricity.

Figure

15. US per capita energy consumption by sector, based on EIA data.

Includes all types of energy, including the amount of fossil fuels that

would need to be burned to produce electricity.

If we

cannot expect low oil prices to favorably affect the industrial sector,

the primary impact of lower oil prices will likely be on the

transportation sector. (Little oil is used in the residential and

commercial sectors.) Goods shipped by truck will be cheaper to ship.

This will make imported goods, which are already cheap (thanks to the

rising dollar), cheaper yet. Airlines may be able to add more flights,

and this may add some jobs. But more than anything else, lower oil

prices will encourage people to drive more miles in personal automobiles

and will encourage the use of larger, less fuel-efficient vehicles.

These uses are much less beneficial to the economy than adding high-paid

industrial jobs.

Part 7. Saudi Arabia is not in a position to help the world with its low price oil problem, even if it wanted to.

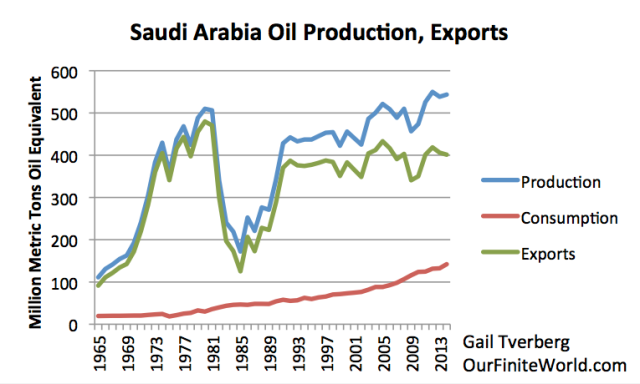

Many

of the common beliefs about Saudi Arabia’s oil capacity are of doubtful

validity. Saudi Arabia claims to have huge oil reserves, but as a

practical matter, its growth in oil production has been modest. Its oil

exports are actually down relative to its exports in the 1970s, and

relative to the 2005-2006 period.

Figure 16. Saudi Arabia’s oil production, consumption, and exports based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 data.

Figure 16. Saudi Arabia’s oil production, consumption, and exports based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 data.

Low

oil prices are having an adverse impact on the revenues that Saudi

Arabia receives for exporting oil. In 2015, Saudi Arabia has so far issued bonds worth $5 billion US$,

and plans to issue more to fill the gap in its budget caused by falling

oil prices. Saudi Arabia really needs $100+ per barrel oil prices to

fund its budget. In fact, nearly all of the other OPEC countries also

need $100+ prices to fund their budgets. Saudi Arabia also has a growing

population, so it needs rising oil exports just to maintain its 2014

level of exports per capita. Saudi Arabia cannot reduce its exports by

10% to 25% to help the rest of the world. It would lose market share and

likely not get it back. Losing market share would permanently leave a

“hole” in its budget that could never be refilled.

Saudi Arabia and a number of the other OPEC countries have published “proven reserve” numbers that are widely believed to be inflated.

Even if the reserves represent a reasonable outlook for very long term

production, there is no way that Saudi oil production can be ramped up

greatly, without a large investment of capital–something that is likely

not to be available in a low price environment.

In the United

States, there is an expectation that when estimates are published, the

authors will do their best to produce correct amounts. In the real

world, there is a lot of exaggeration that takes place. Most of us have

heard about the recent Volkswagen emissions scandal and the uncertainty regarding China’s GDP growth rates.

Saudi Arabia, on a monthly basis, does not give truthful oil production

numbers to OPEC–OPEC regularly publishes “third party estimates” which

are considered more reliable. If Saudi Arabia cannot be trusted to give

accurate monthly oil production amounts, why should we believe any other

unaudited amounts that it provides?

Part 8. We seem to be

at a point where major debt defaults will soon start for oil and other

commodities. Once this happens, the resulting layoffs and bank problems

will put even more downward pressure on commodity prices.

Wolf Richter has recently written about huge

jumps in interest rates that are being forced on some borrowers. Olin

Corp., a manufacture of chlor-alkali products, recently attempted to

sell $1.5 billion in eight and ten year bonds with yields of 6.5% and

6.75% respectively. Instead, it ended up selling $1.22 billion of bonds

with the same maturities, with yields of 9.75% and 10.0% respectively.

Richter also mentions

existing bonds of energy companies that are trading at big discounts,

indicating that buyers have substantial questions regarding whether the

bonds will pay off as expected. Chesapeake Energy, the second largest

natural gas driller in the US, has 7% notes due in 2023 that are now

trading at 67 cent on the dollar. Halcon Resources has 8.875% notes due

in 2021 that are trading at 33.5 cents on the dollar. Lynn Energy has

6.5% notes due in 2021 that are trading at 23 cents on the dollar.

Clearly, bond investors think that debt defaults are not far away.

The latest round of twice-yearly reevaluations is under way, and almost 80 percent of oil and natural gas producers will see a reduction in the maximum amount they can borrow, according to a survey by Haynes and Boone LLP, a law firm with offices in Houston, New York and other cities. Companies’ credit lines will be cut by an average of 39 percent, the survey showed.

Debts of mining companies are also being affected with today’s low prices of metals. Thus, we can expect defaults and cutbacks in areas other than oil and gas, too. There

is a widespread belief that if prices remain low, someone will come

along, buy the distressed assets at low prices, and ramp up production

as soon as prices rise again. If prices never rise for very long,

though, this won’t happen. The bankruptcies that occur will mean the end

for that particular resource play. We won’t really be able to get

prices back up to where they need to be to extract the resources.

Thus

low prices, with no way to get them back up, and no hope of making a

profit on extraction, are likely the way we reach limits in a finite

world. Because low demand affects all commodities simultaneously,

“Limits to Growth” equates to what might be called “Peak Resources” of

all kinds, at approximately the same time.

http://www.theenergycollective.com/gail-tverberg/2277283/low-oil-prices-why-worry

No comments:

Post a Comment